Published on: December 23, 2016

For most people, eating is fun. Who doesn’t enjoy trying a new restaurant with friends, or digging in to a favorite holiday meal? Although most of us look forward to seconds, some kids would happily pass. Whether it’s refusing to try new foods, avoiding entire food groups, or only eating foods of a certain color, brand, or shape, eating issues actually aren’t that uncommon. So what’s the difference between normal picky eating and a kid who has a problem with foods? And if my child has a problem with food, what do I do?

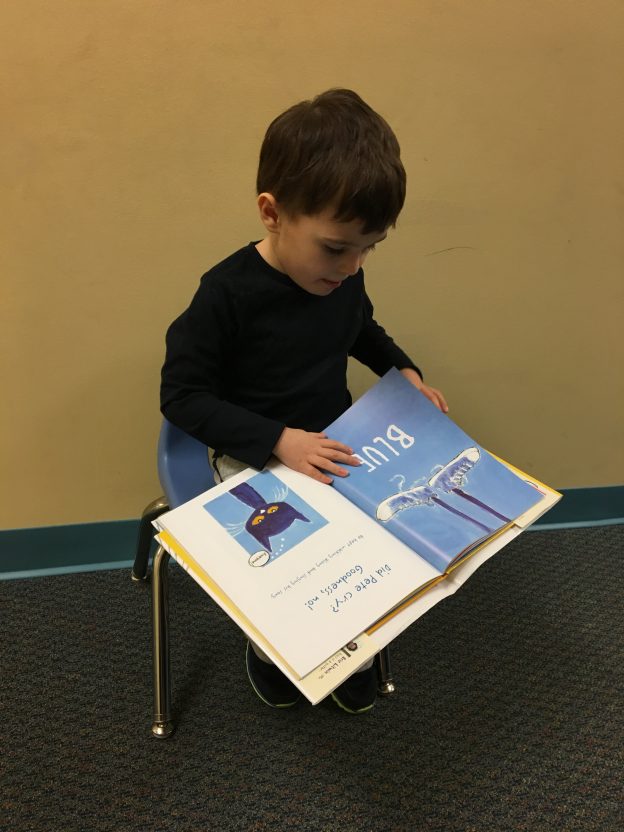

As part of typical development, children will expand and restrict their diet as they age. Small infants will put anything in their mouth, but typically stay where you leave them, which keeps them away from the really bad stuff. Toddlers, on the other hand, are notorious picky eaters but fast movers. This is probably beneficial; because once a child is mobile you certainly don’t want them eating everything they see! Most children experience some eating changes, but continue with healthy development. Picky eating that goes beyond what is normally expected is called a feeding disorder.

A feeding disorder is a medical diagnosis, which occurs when a child fails to consume an adequate amount or variety of solids or liquids to support healthy development. True feeding disorders probably affect between 3% and 25% of typically developing children (Chatoor & Ganiban, 2003; Manikam & Perman, 2000), and up to 80% of children with disabilities (Lindberg, Bohlin, & Hagekull, 1991; Reilly, Skuse, Wolke, & Stevenson, 1999; Williams, Field, & Sieverling, 2010). Not every child who has feeding problems has a feeding disorder. While a feeding disorder is a medical diagnosis, food refusal is a behavior that can occur for many children who do not have feeding disorders.

Food refusal is anything a kid does to avoid eating – running from the table, crying, whining, covering their mouth, hitting the spoon, spitting out food, or even aggression. When your kid is refusing food, everyday events can be supremely stressful. Meals become battles. Trips to restaurants are a distant daydream, and holidays are full of unsolicited advice about how much more your kid would eat if you just did X, Y, and Z. One of the main reasons food refusal persists is simply because it makes the food go away (Bachmeyer, 2009; Piazza, 2008). For whatever reason (preference, testing boundaries, texture issues) some kids will work really hard to avoid some foods. If the most effective way a kid can make food go away is food refusal, they will keep it up. The key to weakening food refusal is making sure you don’t fight this battle.

Although each child’s food refusal is unique to their situation, there are a couple basic strategies all families can use to avoid strengthening food refusal, and offer lots of opportunities for success with new foods.

- Don’t start battles you can’t win

- The biggest mistake you can make is to tell kids they can’t do, have, play something if they don’t eat a food, and then not follow through with it. Never make a promise you can’t or won’t follow through with.

- Confrontation about foods will rarely result in food acceptance. Keep emotion and strife out of mealtime by never issuing ultimatums. Approach new foods as choices, not requirements. Focus on exposure, simple small steps, and lots of good outcomes (praise, second helping of preferred foods, fun activities) for what you want to see more of.

- Expose your kids to lots of new foods

- They are more likely to try something if it is within reach. The more new foods they see, the more chance they have to try something new.

- Make new foods a part of the routine. For example, you could set the expectation that a new food has to stay on the plate for the whole meal. Avoid the temptation to get them to try it – just show them it has to stay on their plate. Exposure can be half the battle anyway.

- Offer rewards for trying new things! Maybe your kid can earn an extra helping of desert if they try a new food. If they don’t try it, make sure it is no big deal.

- If you feed it, it will grow

- Your attention is like food for behaviors. If you “feed” refusal with lots of attention, you can expect to see more refusal. “Feed” food acceptance, nice table manners, and trying new things with a ton of attention! “starve” food refusal as much as possible.

- Act bored when your child refuses food, and talk lots about it when they try new things.

- Start small and stay consistent

- Change does not happen overnight. Pick something small you want to work on, like offering a new breakfast cereal every morning, and keep it up. It may take months before your child tries something new, but every experience takes them one step closer to broadening their palate.

At the end of the day, most kids’ feeding behaviors recover and balance out as they age. Even so, many adults have foods they will not eat, and they are perfectly happy and healthy. Contact your doctor if your child isn’t eating enough to gain weight, is missing meals because of food refusal, is dehydrated, or hurts themselves during mealtime.

Happy eating!

By Laura Melton Grubb, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LBA

For more information on The Shafer Center call 410-517-1113 or email [email protected]

References

Bachmeyer, M. H. (2009). Treatment of selective and inadequate food intake in children: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 2, 43-50.

Chatoor, I., & Ganiban, J. (2003). Food refusal by infants and young children: Diagnosis and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 138–146.

Lindberg, L., Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (1991). Early feeding problems in a normal population. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, 395–405.

Manikam, R., & Perman, J. (2000). Pediatric Feeding Disorders. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 30, 34-46.

Piazza, C. C. (2008). Feeding disorders and behavior: What have we learned? Developmental Disabilities Research Review, 14, 174-181.

Reilly, S. M., Skuse, D. H., Wolke, D., & Stevenson, J. (1999). Oral-motor dysfunction in children who fail to thrive: organic or non-organic?. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 41, 115–122.

Sieverling, L., Williams, K., Sturmey, P., & Hart, S. (2012). Effects of behavioral skills training on parental treatment of children’s food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45, 197-203.

Williams, K. E., Field, D. G., & Seiverling, L. (2010). Food refusal in children: A review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 625–633.