Published on: March 20, 2019

Teaching a child to live and function independently in society – this is a common goal for parents and professionals in the field of special education. Although this is a common goal, most people have a different definition for independence. Is independence accomplished when someone lives by themselves? Does it mean maintaining a job? Can independence mean being able to tie your shoe or make yourself breakfast? In reality, independence is difficult to define because it is different for every individual.

In the field of special education, parents hear a lot of different terms when professionals talk about independence (e.g. activities of daily living, independent living skills, adaptive living skills, functional life skills, etc.). All of these terms mean activities that everyone regularly engages in; some activities you engage in every day. In other words, they are skills that are important to teach to promote independence. A profession in the field of special education that has a large focus on independence is behavior analysis. Behavior analysts study behavior and environmental variables in order to decrease non-preferred behavior and teach appropriate alternative behavior. When identifying skills to teach, behavior analysts ask themselves, “how will teaching this skill benefit this child in the future?” or “will this help promote independence in the child’s life?” Behavior analysts ensure that the behaviors that are taught have social significance and are beneficial to the child. The question remains, how do we go about teaching these skills?

Where do I start?

- Set realistic goals. Before you start teaching these independent skills, you want to think about what reasonable goals you have for the child. For instance, identifying the future goal as completing their morning routine by themselves but setting a short term goal as independently brushing their teeth.

- Teaching independence takes patience. Each skill will take a lot of practice. It is extremely challenging to be completely independent the first time you try something new. Be patient and enjoy even the smallest improvements in independence!

- Start small. Break down a task. For example, instead of targeting the whole task of brushing teeth, target each part. There are many skills that are associated with brushing teeth (e.g. turning on the water, opening the cap to the toothpaste, putting toothpaste on the toothbrush). You can more easily determine progress with independence if you view each step as a separate skill. Perhaps, you can take data on the amount of steps completed independently. Say there are 15 steps to brushing teeth and last week the child completed 2 steps independently and 5 steps independently this week, you can determine that the child is making progress towards independence in learning to brush their teeth.

- Give multiple opportunities to practice. The more opportunities to practice, the faster the child will acquire a skill.

- Set the child up for success. Have the child be successful with doing something on their own by starting with small steps that are already in their repertoire of skills. The child will have more success with acquiring a new skill if they start out successful. Think about doing really challenging math problems: if you start with difficult problems you are more likely to give up sooner. If you start with basic math problems first, the more difficult math problems will seem easier. Behavior analysts call this behavioral momentum.

- Look at every situation as an opportunity to practice independence. Everything a child does in their day can be a time to teach independence. Opening the door, pouring milk in their cereal, and using utensils are all small steps to independence that can be easily incorporated and encouraged each day.

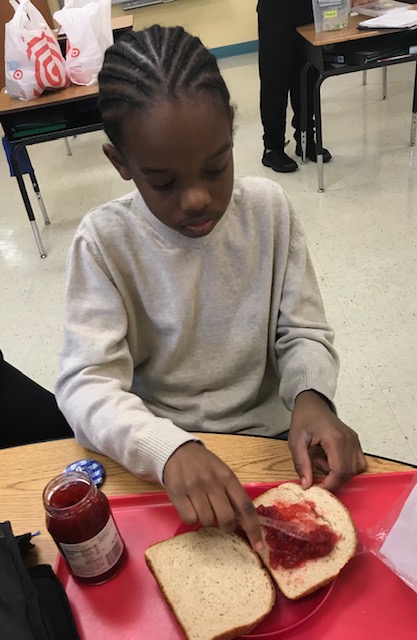

- Reinforce the behavior! Reinforcement can be many different things depending on the child’s preferences: praise, getting to play with their favorite toy following the activity, or even eating that sandwich after making it. Whichever way works for the child, let them know they are doing a great job!

When should I start?

- Start ASAP. It is never too early to teach independence. It may not be developmentally appropriate to teach your child to do their laundry at their current age but you can start by teaching them how to put their dirty clothes in the hamper.

How do I teach independence?

One of the most important things to think about, when promoting independence, is prompting and prompt fading. A prompt is designed to help or cue another individual to perform a desired behavior. Prompts include, but are not limited to, physically assisting someone to perform the task (full-physical or partial physical prompts), using a visual cue (e.g. a written sequence of steps), verbal instructions, or using a gesture (e.g. pointing to the soap while washing hands).

- Before you prompt anything, you want to think about the following:

- What can they already do by themselves? To answer this question, we take baseline data. Baseline data is a way to measure their current level of independence before we implement a teaching procedure. First, ask them to do a task and see what parts of the task they can already do themselves. We do not want to prompt or teach skills that they already do independently.

- Pick prompts that can be easily faded. We want to make sure that we are actually teaching the skill and not just doing the desired behavior for the child. For example, if you are always vocally telling your child what the next steps are, they may start waiting for you to tell them the next steps. Instead have them focus on the things that will naturally cue them to do the next step. Behavior analysts like to use the phrase, “prompting to the relevant stimuli.” Let’s say, a child is in the process of washing their hands. The fact that their hands are wet and the sight of the paper towels should be their natural cue to dry their hands, instead of the verbal command, “dry your hands” or if you were to take a paper towel and wiping their hands for them.

- How to use prompting to teach:

- Prompt fading. When initially teaching a skill, you may need to use a more intrusive prompt (e.g. full-physical prompting) to have the child successfully complete the skill. Eventually, you want to slowly and systematically fade out the prompts for the child to do the skill independently. For example, the first time the child made a sandwich, you had to use full-physical (“hand-over-hand”) prompting for the entire task to be completed. Next time, you can see if the child can complete opening the jelly jar by just gesturing to the jar. The less intrusive the prompt, the more independently they are completing the skill.

- Utilizing wait time. Waiting for them to try to do something independently before you jump in and help can be the most effective, least intrusive way to promote independence. I know it is sometimes hard to wait – it could be their 5th time trying to tie their shoe and they are already running late for school. Before you rush in to help and try to speed up the process, just know that you are providing them with an opportunity to practice independence.

- Practice, practice, practice! As it was mentioned above, the more practice the better!

When they have a skill, what should I do next?

- Check for generalization. Can your child demonstrate the skill with different people and in different environments? For example, after teaching washing hands in the child’s home bathroom, can your child wash their hands in a public bathroom as well? If the skill does not generalize to other people, environments or stimuli, you may need to teach the skill in those settings.

- Using the skill to learn other skills. Building upon generalization, many skills can be used in different situations. Using similar, previously taught skills can help teach new skills. For example, if the child learns to zip their jacket, check to see if they have generalized this skill to the zipper on their lunchbox or backpack.

- Continue to practice the skill. The child may have demonstrated this skill independently a couple of times, but that does not determine if the child will maintain that skill over time. Learned skills should be probed for maintenance following the child demonstrating the skill independently. This means, the child should continue to practice the skill. Luckily, opportunities to practice these independent skills frequently and naturally occur in the child’s daily life.

What if problem behavior occurs?

- Trying new, difficult tasks can sometimes be related to an increase in problem behavior that functions as a way to escape (get away from) the demand. This is a great opportunity to teach advocating for themselves by practicing asking for help or using appropriate language to say something is difficult. We encourage our kids to be independent but we also want to reinforce appropriate communication. If a child engages in problem behavior, the activity/demand should remain in place until the activity is completed or until the child asks to finish the activity without engaging in problem behavior. We want to make sure that escape from the demand is not granted by engaging in problem behavior. If the demand is removed because they are engaging in problem behavior, they will most likely engage in problem behavior in the future to escape a demand.

To summarize, every activity a child does throughout their day can be a time to teach independence. The earlier a child starts on practicing independent skills, the more opportunities they will receive to practice the skill. Even if the task may not be developmentally appropriate for the child at their current age, we can still work on parts of the task. Start by setting realistic goals and breaking down big tasks into steps. An effective way to teach these skills is by using prompting and systematically fading the prompts to less intrusive prompts. It is important to remember that everyone makes mistakes – that is how we learn. Lastly, patience in essential; be supportive and always reinforce their appropriate behavior!

References:

Taurozzi, S. (2015, July 22). Promoting Independence in a Child with Autism. Retrieved from https://nspt4kids.com/parenting/promoting-independence-in-a-child-with-autism/

Cooper, John O., Heron, Timothy E.Heward, William L. (2007) Applied behavior analysis /Upper Saddle River, N.J. : Pearson/Merrill-Prentice Hall