Published on: March 30, 2018

Prior to working as a special educator at The Shafer Center, the term BCBA (Board Certified Behavior Analyst) was foreign to me. I took behavior courses in college and those were always my favorite because behavior is fascinating, but the fact that some people study and work with behavior full-time never crossed my mind. After my first week working with students at The Shafer Center, behavior became something with which I started to fall in love. I felt passionately that I somehow had to pursue studying this amazing science.

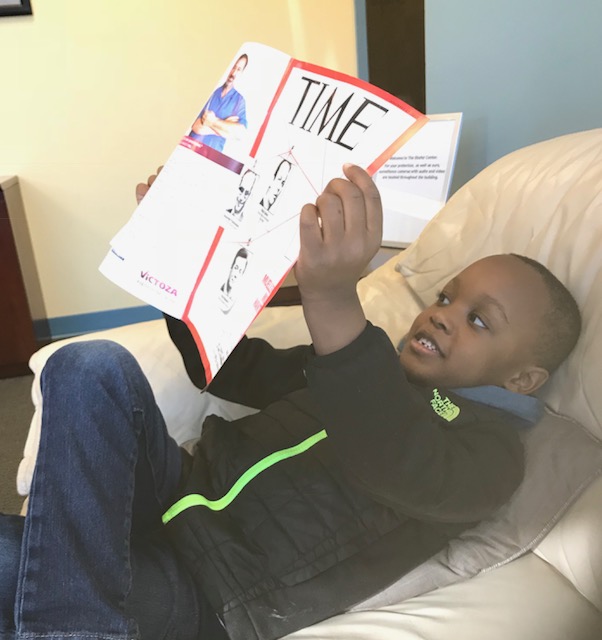

Most people have no idea what a BCBA is and those who do have an understanding of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) might imagine that I’m sitting face-to-face with a kid delivering tokens for 6 hours while they do things like touch their nose or clap their hands. ABA is much more complex than that. ABA is a type of therapy that focuses on improving or changing specific behaviors in a socially significant way. When a BCBA talks about behavior change we don’t just mean changing “bad” or “problem” behavior; we also use ABA to increase appropriate behavior (e.g., communication, academic skills, and self help skills, to name a few). A BCBA studies and applies the principles of ABA to systematically and appropriately make changes in behavior, based on the needs of the client. These changes are done using visual analysis of data. If you’re not collecting and analyzing data regularly, you’re not doing ABA!

ABA for Behavior Reduction

The first thing that we want to do when a child is engaging in inappropriate behavior is identify the function of that behavior. All behavior happens for a reason and by identifying the function of the behavior we can figure out a more appropriate way to access that same function. For example, one of my students rips his papers because he does not want to complete his work. As a result we have been working on him asking for a break, asking for help with difficult work, and finding reinforcers to motivate him to complete his work. Most of our students have individualized Behavior Intervention Plans (BIPs) that encompass everything you need to know about the student and their specific behaviors: the definition for each behavior, skills that we are working on to replace the inappropriate behavior, the schedule of reinforcement the child receives for appropriate behavior, consequences for when the child does engage in the behavior we are trying to reduce, and how we are taking data on each aspect of the plan. We use the data that we are taking to make sure that the BIP we have is effective for the student and make changes to the plan when necessary.

As a special educator, I often work with the BCBA to make sure that the BIP can be consistently followed in the classroom setting because consistency is a key component to the BIP being effective for that student. Following the BIP is not the only way we embed ABA into the classroom. I also take advantage of naturally-occurring events to reinforce, and we teach and assess academic and behavior targets through Discrete Trial Training (DTT).

ABA for Skill Acquisition

Discrete Trial Training is a teaching program that falls under the umbrella of Applied Behavior Analysis. It is made up of 3 parts: 1) the teacher’s instruction, 2) the child’s response (or lack of response) to the instruction, and 3) the consequence, which is the teacher’s reaction in the form of reinforcement, “Yes, great!” when the response is correct, or teaching the target response is incorrect.

DTT is a great way to teach and assess skills that may not be in a child’s repertoire, but are necessary to lead a successful life. For example, one of my students is learning their name, address, phone number, and parents’ names via DTT. We do this by first giving an instruction. Let’s use learning their address, for this example. After the student receives the instruction, they are to respond correctly. If they do not respond or respond incorrectly, we go into teaching. We give the instruction again, “What’s your address?”, and then before the child can respond we give them the answer. Then, we ask the question again and if the child gets it right we praise them and give them a reinforcer, if applicable to their specific program and reinforcement schedule. If they do not get it right, we move on to the next question and re-try that question later in the session.

I also use DTT to teach new concepts in the natural teaching environment, like when asking reading comprehension questions or answering math facts. While DTT is not going to be used in every environment the child encounters, it is important that they gain the knowledge while they are here and learn to maintain and generalize these skills across settings.

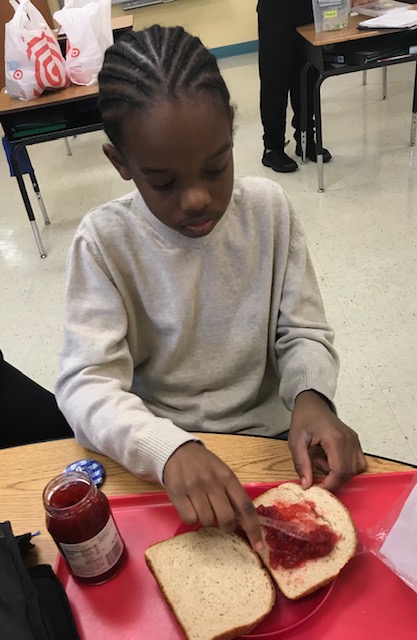

In the classroom it is hard to reinforce each correct response that every child gives so we look at ways to delay reinforcement and systematically decrease the level of reinforcement the child needs to be successful. One way that we do this is by using token boards in the classroom. After the student earns a certain amount of tokens, they can exchange the tokens in for a preferred item or activity. Over time the amount of work a child needs to complete to earn a token slowly increases. Using tokens is an easy way to deliver reinforcement quickly in the classroom without taking away from the rest of the class. Each child earns tokens for different behavior based on their individual plan and what behavior we are looking to increase for that child. This is textbook ABA: reinforce the behaviors you want to see and you will continue to see them. During academic centers time students earn tokens for following directions and completing tasks relevant to the work (i.e., writing their name on their paper, finishing the worksheet, placing the worksheet in the designated Finish Bin). We also work on walking in the hallway in a straight line, raising hands to get a teacher’s attention, and waiting to take a turn. When we remember doing all of these things in elementary school they seem to have just come naturally to us. However, at some point we contacted some form of reinforcement for all of these naturally-occurring school behaviors, and in turn, they just became routine. It is very important for me as a teacher and a future BCBA to teach and reinforce routines that will help the kids be successful where they are now, and in the future.

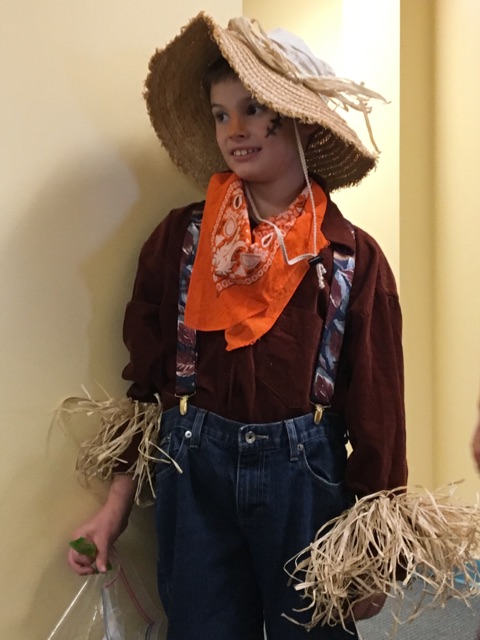

The goal for our students is for them to matriculate to a less restrictive environment. And, one of the biggest questions we ask ourselves when prepping and planning for their change is, “What do the kids need to know in order to be successful outside of our bubble?”

ABA has helped me teach and reinforce the behaviors and daily occurrences one imagines when they picture a more typical school setting: socially, academically, and behaviorally. One example of this is in my classroom we are working on telling friends encouraging words. Every time a student says something encouraging to their friend, they earn a cube. When they have 3 cubes, they get a piece of candy or a toy. ABA can be used in a variety of ways across a variety of settings and skills. If you can identify the behavior that you want to target ABA can be used to help teach a child to learn that skill.

I am excited to further my career as a special educator while pursuing my BCBA certification so I can continue to work with and serve the amazing and diverse population that I hold so near and dear to my heart; the kids that have truly changed my life and how I view the world. With the right tools to succeed, anything is possible. And BCBAs have the best tool boxes.

By: Christine Coffman, M.Ed.